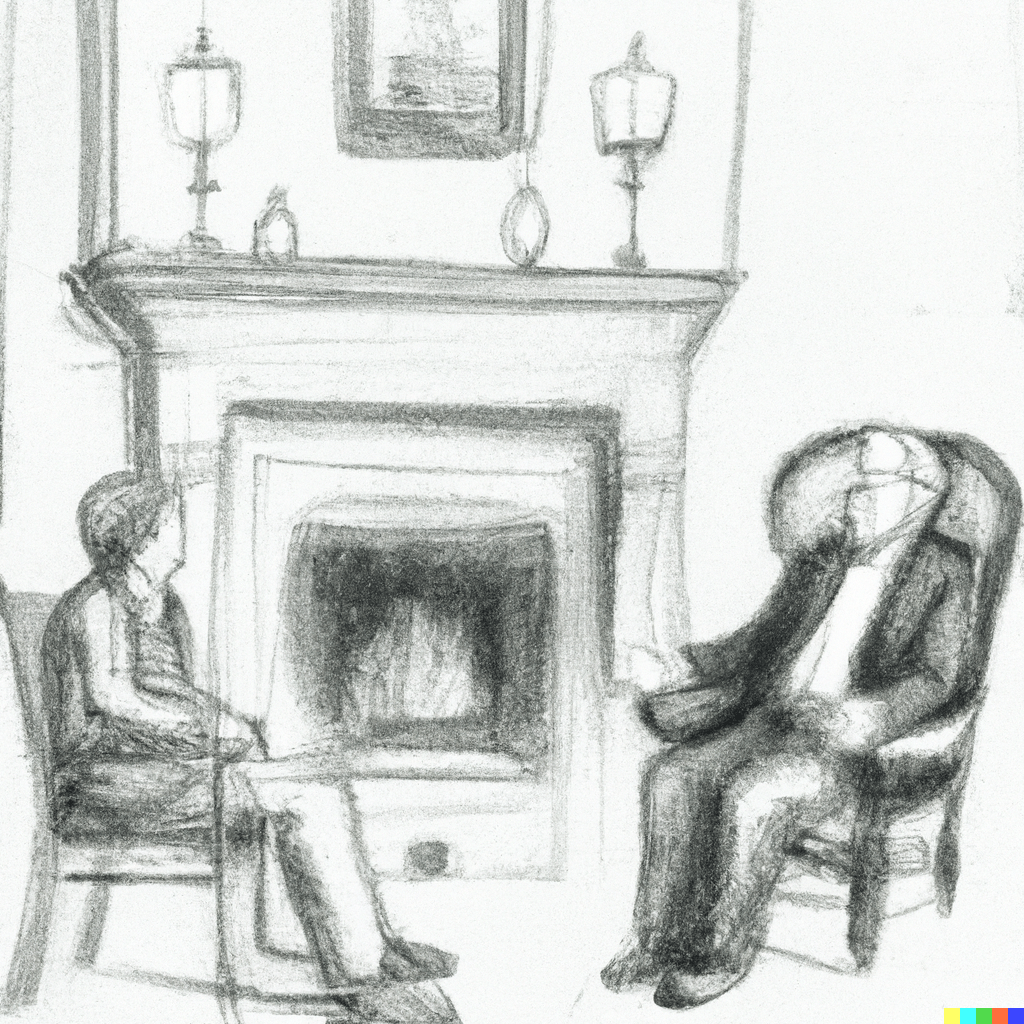

A Father and Son Fireside Podcast

In a warm setting reminiscent of the sitting room in the Roosevelt’s Hyde Park estate, fire burning comfortingly behind them, a father sits talking with his middle-aged son, a conversation so evocative that occasional footage of actual recorded history or animation of concepts occasionally filters through their mind. The conversation ranges widely, but the tenor is one of general disappointment at the current state of affairs and concern that if things are not righted, and with urgency, then humanity will continue paying dearly.

Of course the father and son see the climate crisis as the most pressing issue that confronts humanity. But they recognise its origin, cause, and effect, and thereby its solution, lies within the greater realms and nuance of the human experience. In effect, the climate crisis constitutes little of what they discuss because the groundwork for action lies not in the science surrounding climate change, nor in the innovation to minimise it and ameliorate its affects, but in the social cohesion that is necessary to address it along with the next crises that humanity will undoubtedly face.

Following is a description of what is discussed.

Global inequality

There’s something about humanity at this point in our progress that limits our altruism and good will to other human beings.

Through guilt or empathy we in developed countries react to imagery of the suffering of poor people in poor nations. Some suggest that the reaction is less-so when the skin tone of those suffering is darker. Alternatively, the threshold for the suffering being experienced required to elicit the same level of response may be higher, roughly proportional to the darkness of the skin tone. Of course, a majority of lighter-skinned people refute this.

Nonetheless, that there is a reaction from people to the suffering of the poor, which invokes decision-makers to respond, is encouraging.

However, it must be said that the response tends to be limited to the feeling that all human beings should be free of suffering. For most in rich countries there is an indifference to the subject of whether all human beings deserve a certain quality of life. Often political activists couch this in the terminology of a ‘dignified’ or ‘decent’ standard of living with all the inherent subjectivity.

On thing is true of modern society – although they wish not to be confronted with the suffering of other human beings, to this stage, the majority of the wealthy amongst humanity remain resistant to the loss of any of their privileged quality of life so that all human beings might have a quality of life significantly above subsistence (i.e. mere existence).

Capitalism at an extreme

Elliott Roosevelt was quite right in complementing the sensibilities of the American people in supporting his father’s Presidency, and the pride that American people feel in what they all achieved under his leadership is rightful.

At the other end of the spectrum, Churchill expressed feelings of superiority and condescension when he suggested that the best argument against democracy is a 5 minute chat with the average voter, as he is widely attributed for saying.

There is surely some truth to the contention that in democracies the people get the political leadership that they deserve. Perhaps that even holds true in moderate autocracies, and the degree it holds true is related to the heavy-handedness and willingness of the State leaders to oppress the citizenry and assert a centralised will over them.

If we in the developed world have progressively experienced poorer political leadership since WWII – less proactive to the point where politicians stopped leading and simply became followers of the ‘free market’ while continuing to extract rents from their privileged position through legalised corruption of politics in the form of political donations and extremely advantageous post-political business and career opportunities – the obvious question is whether that is the fault of the people.

In the 80’s the movie “Wall Street” with Gordon Gekko’s famous quote that “greed is good” captured the mood of the period. It initially shocked, but in a manner that we now have come to understand well, it also began the process of normalising this in culture.

At the same time the middle class was hallowed out largely without people noticing that they had traded their comfortable and reasonably secure existence for a shot at riches beyond their wildest dreams. But there are only so many positions in the C-suites of major businesses that pay multi-million-dollar salaries, and not everyone else can work in hedge funds. Someone had to earn the everyday salaries that produced large aggregations of deposits which the Wall St sharks take a bight from as they funnel them through a system that does little more than provide the perception of activity, a thin justification for taking those fees.

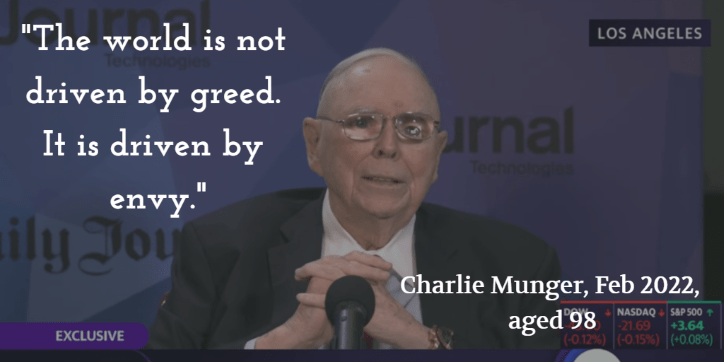

This is well summed up in the words of Charlie Munger, who together with Warren Buffett is the consummate capitalist so much so that they have been asked for advice by US Presidents and have been called on to lend credibility to stabilise markets at times of vulnerability, speaking in 2023 just after his 99th birthday:

“So there is some of this old fashioned capitalist virtue left at Daily Journal, and there is some left at Berkshire Hathaway, and there is some left at BYD, but in most places everybody is just taking what they need without rationalising whether it is deserved or not”.

Incidentally, one of the examples given – in fact, the man he credited for inspiring the actions to which he had referred – was a Chinese businessman.

At the same meeting the previous year Charlie identified the real motivation behind greed, that being envy.

The normalising of greed within our capitalist system meant that it became synonymous with self-interest which had been a concept for several centuries since the grandfather of economics, Adam Smith, identified it as a critical factor in capitalist transactions. But this was a co-option because self-interest has far wider, long-lasting connotations and implications whereas greed is very short term.

Greed for short term gains became accepted and then increasingly venerated, hand in hand with extreme interpretations of the work of Milton Friedman from the early 70’s which said that the sole social aim of a business is to make profits. This was then used to justify an increasingly extreme form of capitalism producing inequitable outcomes, often referred to as ‘trickle-down economics’, which argued that it is beneficial for society that the rich become even richer because benefits trickled down to those below them in social status. Of course, as the inequity grew, most people felt their lives had come to resemble that of hyperactive hamsters on a treadmill working harder and longer to earn the right to squabble for meagre scraps that fell from the table of the societal elite.

Add embedded social immobility through generational privilege, and systemic and widespread social racism from unchallenged histories of colonisalism and/or slavery, into a system which is said to be based on merit, and there is a brewing social discontent seeking to apportion blame. With social safety nets in America significantly less supportive than in most other developed nations, there is a working poor that had not existed since before the Great Depression and does not exist in most other developed economies. Many of the most vulnerable within society resort to extreme survival measures such as selling their blood to the producers of high value blood products.

However, the elixir of extreme wealth as advertised through sophisticated dispersive media, which became omnipresent with the invention of the smart phone and augmented with almost unfettered influencers, has had an intoxicating affect selling American culture throughout the world, especially to the young.

Other anglophone nations, especially, have experienced this cultural drift which pervades society from families right through to business and politics with concomitant creeping up in hours spent working and increasing levels of materialism concomitant with decreasing levels of life satisfaction measured in surveys and decreasing mental health measures.

The COVID-19 pandemic put a punctuation mark in this progression, with surveys of people showing greater levels of altruism and levels of self-care, including seeking more flexible working conditions, but it is too early to know whether it will be a ‘comma’ denoting a pause, a ‘full stop’ indicating a prolonged pause which may or not be a true end, or an ‘exclamation mark’ – an emphatic rejection of the earlier period of extreme capitalism.

Through this phase of human development, the demands on personal time and energy have been unrelenting, and while technology has facilitated greater productivity, the cognitive ‘bandwidth’ of human beings available to process emotions, as well as make short- and long-term decisions, has not increased but has been challenged by the extra drains on energy from modern life.

Between those working day to day for their survival, and those who have been so influenced by the ‘materialism through winning’ elixir, there is significantly less collective bandwidth available for critical thinking. Even of those now looking for answers, many had not been taught and/or practised the skill of critical thinking and are vulnerable to believing dubious sources of information which are becoming increasingly sophisticated at altering facts and influencing opinions and actions.

Thus, to answer the question of whether the people have received the leadership they deserved, the answer must be that, in general, they have not.

Whether society can be blamed for prioritising the accumulating of material wealth over other less selfish pursuits, which also affect our individual and collective quality of life, is a matter of personal values.

What broader society must accept blame for, however, is a willingness to turn a blind eye to the fact and consequences of local, regional, and global inequality; that wealth and high standards of living were attained and maintained from the exploitation and pain of other human beings.

In that way, our contemporary societies are not as different from other or alternate harsh, oppressive, and dominating societies as we would like to believe.

Racism and prejudice – personal experiences

Sadly, my own experience of racism straddles both sides of the divide.

In 2002, with my wife of Asian descent, I lived in Munich as the recipient of a fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (AvHF), after spending the previous year in Montpellier on a fellowship from the French Government. Besides the normal language challenges faced by any non-Bavarian living there, whereby even Germans coming from outside Bavaria would try to disguise it from the famously (or infamously) patriotic Bavarians, I found it easy to live in Munich, in fact easier than in southern France the year before. For my wife, however, whether alone or when we were together, the feeling was very different to how she and we felt moving around in ambient society. She was frequently stared and snarled at while waiting for public transport, feeling unwelcome and unsafe when travelling alone, and conspicuous as a mixed couple when together. The righteousness of some to express the power and privilege in the expectation of others cowering for their very existence was something that she and we had never experienced.

On a train trip into Austria to celebrate our 7th wedding anniversary we were confronted by four middle-aged women snarling at us from the opposite seats as if were dirt. I turned to face off with them, eyeballing each one in turn rotating my head left to right, right to left, and back again, like a carnival game clown. The women chose to continue their vile and hateful stare for at least 5 minutes before in unison they gave a huff and turned their attention away to each other, no doubt to spew hate from their mouths to reinforce each other’s opinions of superiority. At least I stared them down and showed that we are proud and loved us and ourselves – a small victory which I felt we needed at the time.

I, too, soon ran into trouble with my research whereby through stepping on the toes of someone close to the head of my institute, in a truly surreal manner – I asked that the student not keep their dog in the office that we alone shared after it bit me – all of my research was confiscated and locked in a cupboard so that I could not work for the latter half of the fellowship period. During a strange meeting with the technician who had been instructed to confiscate my work and the head of the institute they denied it and undertook to look for my work. I had, in fact, already found my worked locked in a closet outside her lab, but there was no use in my liberating it until the final night of my fellowship as I could not access equipment necessary to conduct my research.

The institute head’s dictatorial manner was confirmed when he told me that I had come into “his house” acting as if I was God’s gift to science. Sadly, a man of Arabic descent who was head and shoulders the best researcher there was being deceived into thinking that he would succeed him and become the head of the institute. Even the students knew he had no chance of that, prejudicially saying that he could not hold such a high position in Germany because his language skills after 30 years of living there were not ‘good enough’. Instead, the much less-established female colleague that I was collaborating with informed me that she had been promised the job. This colleague also said to me on multiple occasions that she was dumbfounded how a mutual colleague, who was born in Germany and whom she had studied with for her undergraduate veterinary degree, could possibly hold the high position she held in the Australian public service.

On the one hand it made me realise that Australia had progressed significantly further than Germany, but I knew this was not the case if you incorporate colourism and that was underlined with what had occurred in Australia in the lead up to the 2001 Federal election, but I am skipping ahead.

I kept the AvHF informed of what had occurred and they were extremely apologetic. An officer’s handwritten note on the responding letter said that sadly this happens all too often in Germany and that they are attempting to lead change to address it.

Living in Germany was the first time I came to understand the waste of human capital that comes from the interaction of prejudice and migration. In my institute there were lab technicians that were doctors in their home countries in eastern Europe before migrating to Germany who would never practice medicine again. That is a loss for Germany as well broader humanity, not to mention for themselves and their families.

The visa that my wife was granted to accompany me did not give her the right to work in Germany. In France her visa did but language was the barrier there to her finding a job. With cosmopolitan Munich being the centre of multinational industry, language was much less an issue. However, my wife soon learned from human resources departments that she would not be considered for a job unless she already had a visa that permitted her to work, and she was told by the Germany visa authorities that she could not gain that visa unless she had a job offer. The perverse circularity of the situation was no secret to anybody.

As we came directly from France my wife had not worked for a year and the impact from feeling isolated threatened to shorten my fellowship period even before it started. In a stroke of luck, as well as resilience and ingenuity, however, my wife managed to bypass local HR staff to speak with a manager advertising for someone to work in his multinational team which worked in English on a pan-European project. After interviewing, she was offered the position and their HR department then had the job of securing the appropriate visa. We learned that this was an all too rare occurrence.

To concentrate on these negative events would be unfair, however, to the effect of leaving an inaccurate picture of our experiences in Germany. The AvHF was an incredibly generous organisation doing an enormous amount of good to progress global science and culture. All fellows and accompanying partners were taken on a 2-week cultural tour of Germany where we learned about German culture especially during the cold war, though less so about Nazism, perhaps understandably. After all, there is plenty from that era to visit and learn, and I personally visited Dachau multiple times ensuring that every visitor to our home that we had through the year also saw the concentration camp museum.

We were incredibly fortunate to be offered at a significantly reduced rent a nice apartment in a beautiful home owned by fellow academics in one of the nicest areas of town. We entered through a side gate and even today on Google Earth Street view detail of this street is blurred because the neighbouring property on that side is the residence of the US Consular General in Munich. Being early 2002, just after 911, there were machine gun-carrying guards outside their residence and I was always careful to slowly claim my keys from out of my pocket. One day, however, coincidentally just as my visa had expired, we were stopped by police after I had roused suspicions of the guards by taking a photo from outside of the corner of our apartment showing the bare vine that crept over our apartment while pristine white snow lay on the ground. Before my welcome was rescinded by the tyrannical institute head, I had the pleasure of walking daily through Bogenhausen and across the Isar River to the institute on the other side of the English Garden.

While there were those who showed their meanness, there were more very keen to show their friendliness and would help us by very willingly switching to English when it became clear that our German was still rudimentary though my wife was sponsored by the AvHF to undertake language course and was becoming quite proficient. We have always remembered how even elderly people were keen to assist us in English, and now being aware of the story of Schacht and how he lived his final years in the area with his second wife, I cannot help imagine what if one of those lovely ladies that helped us on occasions might have been Manci Schacht, or the daughters she shared with Hjalmar, Cordula or Konstanze.

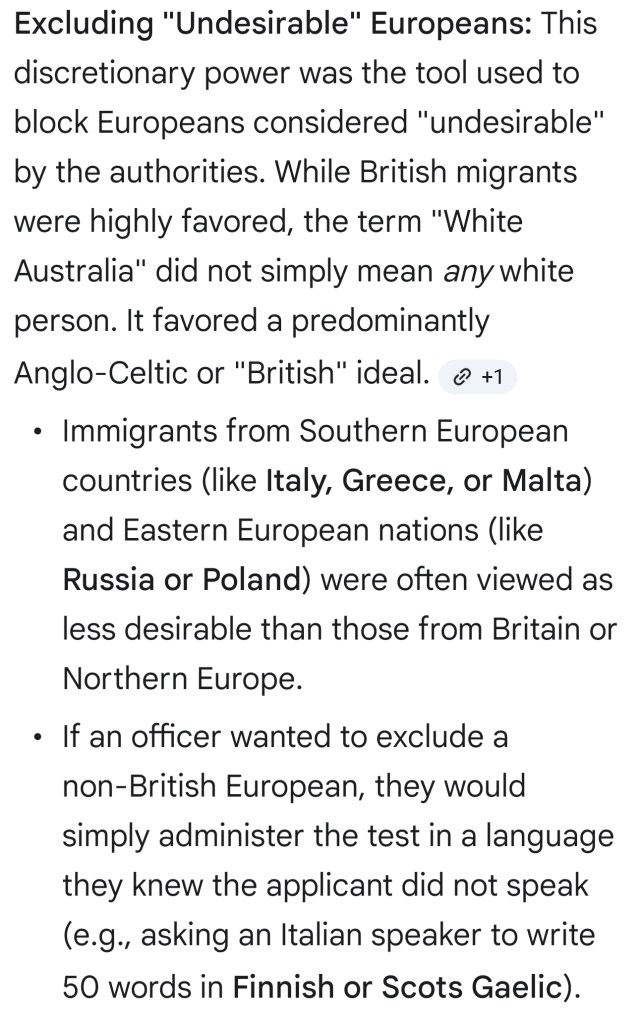

So too would it be unfair to only discuss our experience with racism and prejudice in central Europe, even though its relevance is clear and long-lasting given a world war was fought there ostensibly on the basis that racism and the consequences of it are evil, when we have lived the majority of our lives in a colonialised nation that has itself seen frontier wars against its First Nations peoples and where a migration policy of selecting only for ‘whites’ was maintained for over 100 years. I speak of course of Australia.

I was, in fact, deeply embarrassed to be Australian as an AvHF Fellow mixing with academics from throughout the global community in this period for our own latent racism had been highlighted for the world to see during the Federal election the year before. A deeply unpopular Prime Minister was able to turn the tide and win re-election by being seen to be tough on brown-skinned illegal immigrants who attempted entry on non-sea-worthy vessels. Almost to underline the lack of scruples by these brown-skinned ‘aliens’ who would do anything, use anything or anyone at their disposal to gain entry, including risking the lives of their own children by throwing them into the water to force the hand of the attending rescue ship, this story was maintained right up to the election even though it quickly was disproved and known to the government.

My simple response to other AvFH Fellows was to express my embarrassment and suggest that it reflected as poorly on Australian people as it did the conservative politicians who used the latent racist attitudes of white voters, and naivety of more recent migrants who were compliantly trying to assimilate, for if their hearts and minds were more open then they would have rejected the government for using such evocative and divisive tactics. This led to a period, which continues today, where illegal immigration is a ‘hot button’ topic that the political left lacks the courage to right out of fear implications at elections which has resulted in terrible treatment of people seeking a better life, many genuine refugees, often in contravention of their international human rights.

Of course, this issue is not now limited to Australia, but the ‘Australian solution’ of being so tough on the migrants to act as a deterrent has been exported to many other countries including in Europe.

I was born into a family with deep pride for its colonial history in the township of Innisfail in conservative rural northern Queensland, known for being a major centre for the sugar cane industry. I grew up around racism and was taught to be racist by my most important mentors and by the white-dominant cultural system that I was raised within. In school, even though we shared our classrooms and school grounds with First Nations children, the version of “Eenie Meanie Minie Mo” that I and other children taught each other to select who was ‘in’ included the vile racist ‘N-word’. I do not recall ever being reprimanded or corrected from using the word.

I never knew its meaning, but that is irrelevant, and I can only assume now that the First Nations children would have been taught that it was a deeply racist and hateful word.

I was only taught to be racist. I was not taught how not to be racist, and I certainly wasn’t taught how to be antiracist.

In this environment, it is hardly a wonder, then, that as a teenager it was a common occurrence when with extended family – camping or vacationing over Christmas – to listen to tape recordings of a famous racist comedian of the time, Kevin Bloody Wilson. His most memorable ‘song’ for my family was “Living Next Door To Alan” which captured the ill-feeling of the period towards the initial stages of reconciliation and restoration of the rights of First Nations people to access their lands which were obliterated by the British and the first migrants whose descendants, with some sort of romantic nostalgia, prefer to refer to them as colonialists.

The song told the story of a First Nation family that used these rights to claim land in the most expensive street in Australia next to the richest man in Australia then, Alan Bond. To evoke extra anger from his mainly white listeners, Wilson had the Aboriginal subject say that it was “Dead fuckin easy!” which I especially remember family members singing with vitriol in the ridiculous assertion that First Nations peoples are benefitting enormously from white colonisation well beyond that of white Australians, which contradicted the obvious reality which I had witnessed all of my life. The final line stresses the divisiveness and hatred in the lyrics where he sings, in first person voice of the First Nations man, “At least we ain’t got fuckin coons livin next door to us!” to stress how nobody would want a First Nations family living next to them, not even other First Nations peoples.

In my view you would be hard-pressed to find a more hate-filled piece of writing. This record was sold Australia-wide and for this album Wilson was venerated by the peak Australian music industry awards in 1987 receiving an ARIA for “Best Comedy Release” and was nominated for “Best Selling Album”. The song can still be downloaded from YouTube, and one version available there (last accessed 26 May 2023) – which advertises Wilson’s website address for the sale of his comedy and merchandise – includes a racist ‘joke’ told between lyrics that Michael Jackson took with him when he toured a monkey for spare parts!

The face of migration to Australia changed in the 80s, championed by a left-wing government, so that by the 90s there was a growing backlash against Asian migration and apparent ‘political correctness’ which said that the white majority should not be called out or made to feel immoral for objecting to the changing racial composition of the nation. Asian immigration has a long history in Australia, which even predates British ‘colonisation’, but the long-running White Australia Policy – which limited migration to essentially Caucasians – kept numbers low and the early Asian migrant families had very intentionally minimised their cultural difference, i.e. assimilated, to minimise offense and castigation.

The new migrants, however, were conspicuous in number and cultural influence, and soon the objectors found their ‘champion’ in the form of a fish and chips shop owner from Ipswich in Queensland named Pauline Hanson who told parliament in her maiden speech that “Australia was in danger of being swamped by Asians”.

I had fallen in love with my wife at university and I knew that, because of endemic racism, our relationship would cause me to lose some of my social standing in my hometown and within my immediate and extended family given that she was both a woman of colour and of Asian descent. This was underlined for me, especially, because when I asked my mother three years earlier whether it would be okay with her and Dad if I brought home a girlfriend who was of First Nations background, whom I fancied then at university, she responded: “obviously we would prefer if you didn’t”.

In some ways I thought that my parents considered my wife being Asian was not as bad as could have been if I did marry a First Nations woman.

Over those early years of our relationship, sadly, we encountered racism constantly within my family. A cousin who I deeply admired said that he wouldn’t eat anything touched by a Thai person. Other cousins proudly told me they were Hanson supporters and denied that she or they were racist. That Kevin Bloody Wilson tape continued to be played every Christmas.

Racism is omnipresent in my family culture, it is systemic.

The most poignant event happened during a Christmas vacation just after we were married when my sister-in-law called a shop assistant who did not serve her promptly enough for her liking an “Asian bitch” when recalling the experience that evening to extended family. We walked out in disgust and what ensued showed that our family would never be the same again. My sister acknowledged it was racist but my mother denied it in a surreal debate which left my wife in our room crying wanting the conflict to be over, and me walking out of the house to be alone because that was how I felt stuck between realities that were supposed to love and support me. Then my mother, thinking that she needed to calm the situation, came to hug me and instantly I could feel her hard coldness and that she could not emotionally connect with what I was experiencing, her enormous heart which had nurtured me all my life completely blocked by bitter hatred, by racism.

The next morning my sister-in-law was deeply hurt at the suggestion that she was racist and was packing to leave. It threatened to ruin everyone’s Christmas and it was all our fault – we were too sensitive was the majority opinion. We were coerced to go and apologise to my sister-in-law for upsetting her in deference of staying together for a family Christmas.

It was to be one of the last Christmases we would spend together as a family as I realised that our relationships had altered irretrievably, that continued contact always involved the risk of my wife being hurt more by bigotry, which I really wanted to avoid when we had children, and that these tensions had joined together with deep pain and trauma at being brought up in a harsh family farm environment creating a family culture that was toxic. Truly accepting that, however, was a process that took many years of me learning to stop trying so hard to have them understand and accept us.

Although I face this issue less so these days from my family because of this distance from them, I still have some interaction with my parents which, sadly, always presents a challenging situation. In recent years they have said and done things which has and will remain with me. On a recent New Years Day they observed my sons carrying out a cultural ritual of bowing on the floor in front of my wife’s parents showing respect and I overheard their outraged discussion afterwards. They have told me a story on numerous occasions of how the President of a sporting association of which they are committee members started a meeting with an acknowledgment of country to pay respect to First Nations peoples, which is standard now throughout Australia, thankfully, but to which they objected indignantly with “we don’t want that shit here!” making the woman cry. Most cuttingly, my father rhetorically told me “Who would want to live next to Indians!” not long ago which really made me confront a truth that I had not been prepared to admit previously – that he must feel some level of personal shame when in public with my family, or with my wife’s family and many of our friends, as anybody who shared his views must when with people who most in our society would easily confuse for being Indian.

Overt events of racism are what we tend to remember most and what gains the most attention in the media. The truth is, however, that these are not the most common forms or incidents of racism.

In my experience, both when I was young and insecure trying to find my own safe place within society, while knowing I was well within the white majority, and as an adult as I became increasingly aware of its impacts on minoritised people and especially on my wife and consequently our family, most often racism is expressed in degrees or shades, whatever metaphor for subtly and nuance is preferred or meets the context.

I think the most accurate way to describe it is that racism, prejudice, and unconscious bias interact with ‘thresholds’ – thresholds in relation to stimulus – that determine whether a reaction or a response will be invoked. It even intersects with shades of skin tone based on the amount of melanin in the skin often referred to as colourisation. This is why the pervasiveness of systemic racism is so difficult to prove at an individual or case-by-case level yet it is clear in topline statistics in almost all aspects of society.

Consequently, the great majority of the individual acts of racism carried out globally on a daily basis is plausibly deniable.

In truth, many of these acts will be imperceptible even to the object of the bias, and the degree to which someone is perceptive of these biases directed at them is related to their prior experiences and teachings.

Their subtly, however, should not be mistaken for insignificance, for the worst effects of these racist acts are cumulative so that they build up in the psyche of those prejudiced against perniciously impacting feelings of fairness, belonging, and safety.

I will demonstrate with a personal experience, one for which I personally carried a great deal of shame over a prolonged period.

My wife underwent an emergency caesarian section during the birth of our first son. After 18 hours, 6 hours of active labour, the birth was not progressing and my wife was becoming exhausted. Past midnight we were in a birthing suite of a private hospital, my wife mostly asleep, and me sitting in the dim light listening to the faetal heart monitor attached to our unborn son which showed that he was in distress. With each contraction his heart rate would slow so much so that it sounded like a steam train struggling to pull over the crest of an incline. When it sounded to me like it was getting dangerously close to stalling, I went to speak with the head nurse at the front desk asking for confirmation that the sound that I had been listening to with increasing concern was that of our baby’s heart, showing my clear concern.

The nurse responded, “yes, I had been thinking about calling the doctor. I will do that now.”

The question that can never be answered, not even if the nurse were asked the next day, if she could get past the natural inference that her judgment might have been influenced by factors other than purely medical, so that she answered honestly, is whether a higher threshold to become concerned might have been applied because my wife is of Asian descent.

When the doctor came, I was given the choice and I consented to an emergency caesarian. Our son took a while to take his first breath while the paediatrician was attending him, long enough for the experienced midwife to show her anxiety and mutter quietly, “c’mon little fella, breath”. For those few seconds afterwards, I was terrified and was already kicking myself for not going earlier to speak to the nurse. That, however, is not the main source of my shame.

Our son was with us in my wife’s room for his first few hours, as is usual, but we were both exhausted and my wife had struggled in vain to feed our son. After an attempt to feed him, I placed our son in his crib and we both fell asleep. When we woke our son was not in the room and I was told that he was in heated crib because he had not been covered properly and his body temperature was low. My wife, also, had a low core temperature and was soon under an insulated blanket blowing warm air on her.

Until this day I carry the shame that our newborn son might have had a serious setback or even died for my mistake in not covering him properly when he was already weakened. It was not really until later years, however, when I truly began to understand how unconscious bias from racism happens in society that I realise we should have had more attentive care from the nurses given the complications in birth, especially since we were first-time parents and we had paid for that care in a private hospital.

Again, would they have been more attentive if we were not a mixed family?

What we also remember clearly from the period was how the nurses frequently commented on our son’s “lovely skin”, telling us that there was no chance of confusing him with the other babies in the nursery, yet to our inexperienced eyes the difference was imperceptible. The point is that to the nurses there was a difference the moment our son entered their care, and describing his skin tone in a positive manner is no indication of what effect, if any, that had on the care he and we received given their experience at dealing with new and vulnerable parents and knowing what were the right things to say to be seen as caring and attentive.

It is all the more remarkable that we never really allowed ourselves to think of these events in these terms for such a long time since when we were in Germany a couple with whom we developed a friendship, after meeting them through the AvHF, had a truly frightening and alarming experience having their first child there. The Chinese mother and Moroccan father were given precious little assistance in the hospital after their baby was born. The nurses essentially poked their heads in the door and asked in German whether they were okay and were dismissive and impatient if they responded with anything other than a simple “yes”. However, their baby barely fed for the first few days and things only turned for the better when the mother learnt how to breastfeed through a book that her husband bought in the library of the hospital. Being the years before ubiquitous internet, that book literally became their primary source for baby care.

Having these personal experiences, I am entirely unsurprised when I hear or read of statistics showing clear inferior birth and general health outcomes for minoritised people. At a personal level, I am also well aware that my wife and I were privileged to be in a private hospital.

How can one, therefore, apportion the impact of racism or colourism through their life?

What is an appropriate time to wait at a counter, what is the threshold for gaining the attention of a server, or how can anyone know whether the server noticed that you were waiting before others of lighter complexion?

Why is it that colleagues’ work is regarded more highly so that perception of cumulative impacts in workplace performance are not seen as valuable as those colleagues’ who received higher value rewards including bonuses and promotions?

Why was your application to rent a home unsuccessful when you are an executive with a high salary with a demonstrable history of continuous work and responsible rental stewardship?

Did Herr Hoffman, the head of my institute in Munich, develop an immediate dislike of me because of who was sitting next to me when we met for the first time, that being my wife? Did it lower his threshold for becoming aggravated with me, in conjunction with my other traits which he clearly disliked, and how did these intersect?

Once alert to and understanding of how racism and prejudice works, it can be seen everywhere, yet it is always impossible to know, and thus prove, exactly how, when, and where its impacts are at work.

Those who are subjected to racism are, at the same time, told that it is they who have been applying a threshold too low or inconsistently – that their threshold for sensitivity, to have hurt feelings or to become offended, is too low so that all in society has come to ‘pander’ to this too low threshold through a societally enforced ‘political correctness’ which only ‘woke’ individuals have the desire to abide by with ‘virtue signaling’ which is circularly reinforced amongst a community of ‘wokes’.

All of this ‘performative’ reinforcement is rejected, according to this mindset, by the shrewd conservatives – ‘salt of the Earth’-types that exist in the mythology of nearly all nations or regions – on the basis that ‘wokes’ are idiot do-gooders who have no understanding of the ‘true’ (usually harsh, often misogynistic) underlying nature of human societies so they will declare openly a refusal to expend energy caring about whether they emotionally offend or hurt others. This asserts a narrow vision of society within such people and leads to them acting with more prejudicial and biased behaviours, potentially even with an agenda to counter the efforts of the ‘wokes’.

There are always any number of reasons available to give for why daily decisions of relatively minor significance are made, and younger people tend to prefer to be optimistic and believe that intentions of others mostly are fair and reasonable. Moreover, younger people tend to be more gregarious and do not wish to dwell on issues which might be divisive, often because they do not want to feel different or excluded in any way. Young people, most of all, want to feel and believe they belong.

By the time a person who has continually been the subject of prejudice reaches middle age, however, the impacts of all of these continual decisions made upon racially dependent thresholds have accumulated and affect them in deeply impactful ways including career advancement and position within society, and ultimately affect feelings of belonging and safety stemming from how they perceive others view them and even how they view themselves. The latter is especially critical because with all these decisions, each one subjective, nebulous, and deniable, and often explicitly denied when concerns are raised formerly and/or informally, there is a continual voice in the back of their head saying, “Maybe it really is me; Maybe I’m just not good enough; Maybe I do not deserve… [whatever it is].”

Few human beings innately have or learn such extreme self-belief that they never engage in self-doubt, and most who do not probably have some form of psychosis. It is entirely predictable that the self-confidence of, and the trust in the system of, the majority of minoritised people will have been broken through a lifetime of living with racism.

This is the corrosion to society caused by racism, and its affects are profound and widespread.

In my experience, most members of the white majority in society fall within two camps – those who deny the racist character of society and thus, of themselves, and those who recognise that racism is a problem, many considering themselves sympathetic, but who believe it does not affect them because they consider they do not personally experience racism. However, I take issue with that view because I have come to realise that I have more experience of overt racism living in a white-dominant colonialist nation than my wife of Asian descent, and if most other Caucasians stop and think they will realise that they have a broad experience of racism, also. The point being that one does not have to be the object of hatred or prejudice to experience racism.

I realise some might prefer or consider it more appropriate that a Caucasian use the phrase ‘experience with racism’ above ‘experience of racism’, but in truth I think it is unnecessary and unhelpful semantics.

I will share one of the most overt acts of racism that I have experienced. In my first professional job immediately after completing my PhD I worked for a public service organisation. One day walking with a senior colleague, second highest in the hierarchy at this facility, I was expressing concern for the local inhabitants of a Pacific island who were receiving the full brunt of a category 5 cyclone. My colleague responded that my concern was unwarranted because “there are only coons and grass huts out there!” Although I was raised with omnipresent racism, I was shocked to hear such a hateful comment in the work environment from a senior colleague, so I did not manage to voice my outrage or even disapproval. In shock, I was rendered speechless and then felt guilty and complicit.

A short time afterwards I was in a photocopy alcove with two other (Caucasian) colleagues besides the same senior officer when a member of the secretarial staff came looking for me and the other junior colleague who was with me. A technician from our former university department where we had studied together for our postgraduate degrees in microbiology/virology was calling as they were cleaning up the walk-in fridge and wanted to ensure that if there was any materials we left there that they did not represent biohazards. After we told the secretary that we left nothing behind, the senior colleague told us “They should just suck up the material and inject it into some gooks – there are enough of them out there now!” I don’t know whether the others were in shock but this time I was ready for it and I informed him that he should not assume that everybody agreed with his vile opinions. I walked off and immediately reported the incident to my superior, but to my nowadays regret, I chose not to take further action as I was only early in my career and was concerned about the impact making a complaint would have.

While this was particularly shocking, in my early years in conservative northern Queensland it was my common experience to be a part of Caucasian groups which openly engaged in shared racism. I grew up with the hushed, on the other side of your hand discussions about ‘abos’ after a quick glance to see who may be near enough to hear, and I heard the jokes or hateful impersonations made when none of the targets of derision were present.

I concede that not every person will have as much experience of racism as I do, and that will depend on social circles through life and/or the level of endemicity throughout regions.

Even those who grew up in less conservative social circles and/or regions, surely, also have reasonably frequent experience of racism. One must wonder whether loyalty to our closest early mentors – close and extended family, coaches, teachers, performers, colleagues, and bosses, etc. – is an important impediment to acknowledging experience of racism.

The recent example of how colleagues of Australian First Nations journalist Stan Grant, along with his employer, failed to support him in the face of racist onslaught, shows most non-First Nations people are still incapable – individually and collectively – of confronting the truth of their experience of racism and thus learning how to respond.

Eliminating racist division and prejudice from our society is highly dependent on the dominant majority, Caucasians in former colonialist nations, becoming a lot more responsible for acknowledging racism when they experience it so that they can be a part of – and when necessary, lead – appropriate responses to it.

The most important element in fighting endemic racism, in my opinion, is for everybody to become responsible for making it clear that the racist is in the minority and will increasingly be minoritised, themselves, if they persist with their hateful opinions.

Racial, prejudicial, and otherwise divisive opinions circulate and grow when people feel free to express them – free not just, or even mainly, because of permissive laws, but by social norms and standards. A comment about “ticking a diversity box” or against “affirmative action” might seem innocuous and harmless when the target of the comment cannot hear, but people get the message that it is socially acceptable to spread such ideas. Nobody knows what that person or the next person who receives those ideas will do with them – will their dislike grow to hate, and what will they do with their hate?

The truth is that whenever a racist act occurs, everybody who has participated in spreading divisive ideas shares responsibility for that act, irrespective of how minor that act of spreading division might have seemed.

Finally, there will always be a minority who seek to play up differences amongst humanity for their own political advantage, often to scapegoat and deflect attention from their own lack of leadership abilities and progress. Real leaders seek to unite not divide, and our societies – the human beings who make up societies – must be shrewd enough to associate attempts at creating division with self-interested power grabs so that they are promptly dismissed without damaging social cohesion.

A responsible, well-regulated media is critical.

Corruption of political processes

That democracy is ‘under attack’ is a common refrain at present. Most attention focuses on interference on the basis of geopolitical contests and frictions. As highlighted during the WWII era, this is not a new event, even if the sophistication of the tools employed are ever increasing, and it will always be the case while there is aggressive competition between peoples from different geographical regions.

This is not the only corruption of political processes, however, and in many ways it is not the most serious even if the other corruptions are largely forgotten or at least overlooked while attention is diverted towards ‘enemies’.

No democracy has solved the problem of how to ensure that parliamentarians serve the interests of their constituencies, and therefore broad humanity, over the special interests of the few that act at the level of the political party or the individual politician.

Through the history of democracies, the most powerful have not sought ‘higher office’ for themselves. No, for most that would seem like much too much hard work and effort, even if that effort were totally directed towards furthering selfish outcomes above the progress of broader humanity. Instead, those truly powerful through virtue of their wealth have sought to influence decision makers by a range of instruments at their dispersal, either directly through investing some of their own wealth to gain favourable outcomes which will grow their wealth even more, or indirectly by owning businesses through which they can influence outcomes.

Many a story has been written about illegal forms of corruption such as bribery. While dramatic, these are significantly outweighed by the legal forms of corruption that permissive democracies have allowed in the form of political donations to parties and of extremely favourable post-political careers and contracts in the private sector or in the political lobbying industry.

These corruptions have led to the interests of wealthy superseding the interests of broader society and humanity, have led to growing societal inequality, and have severely hampered international responses to crises especially the climate crisis.

While legalised corruption has grown with the size of political donations and the lobbying industry, in less contested policy areas the lack of interest shown by politicians to actually lead has had serious impacts. As politicians on both sides of the aisle (left as well as right) agreed that the capitalist market is the best arbiter of capital allocation decisions, it became accepted that corporations and individuals within society would take the lead on all areas of innovation, meaning that areas outside or of lesser importance to markets would be largely forgotten.

In other words, politicians as a group largely relinquished their roles as leaders within society, yet they did not relinquish their positions nor their salaries, even if they were fractions of their post-politics salaries.

In effect, the market arbitrated their own roles as leaders – if there was no economic payoff to them as individuals or as a political party, then it was wasted effort to concentrate on these policy areas.

It is in these forgotten areas where lies the greatest dividend and benefits to society and broad humanity.

The press has been referred to as the fourth estate of democracy given its critical role in framing and facilitating political debate in an open and objective, non-partisan manner. Nowadays, however, the traditional role of the press is strained by other forms of dispersed media created and consumed on ubiquitous electronic devices, especially smart phones. Newsrooms have had their budgets continually cut and staff numbers reduced and consolidated which has impacted the quality of investigative journalism and deeper analysis. Ownership of the press has realised a profitable business case for monopolising the content that groups – based on demography and/or ideology – are exposed to thereby reducing the breadth of opinion to which people are exposed and hardening opposition to other views when they encounter them. This has been aided by pervasive, sophisticated information technology which at the same time has been more covert.

Consequently, there has been an erosion in the level of trust in the role of the media in society and skills at discernment and critical thought have generally diminished in society.

People tend to become stuck in echo chambers with other like-minded individuals and have narrow perceptions of what is reasonable, or even what is truth, and thus are highly susceptible to being influenced by actors which seek political gain. Moreover, while not recognising their own intellectual constriction, people are increasingly pointing it out when they observe others stuck in different echo chambers.

Clearly such a system is corrupted as an instrument for objective political processes, and it is eminently corruptible for specific political goals especially when intersected with the corruption of the political system for personal gain within an increasingly extreme capitalist system.

Such a level of societal polarisation has occurred in past times, and can be ameliorated if the corruption of the political process is acknowledged and addressed via regulation of political interference, and especially of political donations and other conflicts related to politicians, and of the media.

To do so will require a level of honesty and sincerity that has become rare, especially in the anglophone world, since the death of FDR.

What separates modern capitalist societies from fascism?

Fascism is an ultraconservative ideology best known as justifying aggressive actions by especially Germany against its neighbours leading to WWII. Fascist regimes have had variable ideologies borne mainly of the political circumstances from which they derived their power, but these features were common: aggressively nationalistic and misogynistic, opposed liberal individualism, attacked Marxist and other left-wing ideologies, scapegoated minorities especially along racial lines, self-appointed arbiters of national culture and/or religion, and promoted populist right-wing economics.

Historically fascism has been associated with economic disturbance especially when it was felt disproportionately or inequitably across society.

In recent years there have been alarming incidences of ultraconservatism especially in America. There has been insurrection due to the outcome US Presidential election being contested by the incumbent such that a large proportion of the population considered the following Biden presidency illegitimate. The populist fervour that the former reality television personality-turned-President, Donald Trump, created has resulted in a host of political aspirants who initially rode his agenda and wave of populism to gain higher office, and who now attempt to be even more conspicuously conservative.

Media that is not just complicit, but elements within it that have taken on the ultraconservative platform as a business strategy to drive profits, have created echo chambers for amplifying this ultraconservative ideology.

One recent example of the consequence of this is seen in the US state of Florida where strict, but apparently arbitrarily or haphazardly applied laws, introduced by Governor DeSantis in the lead up to his bid for the Republican nomination to contest the 2024 Presidential campaign, have been used to ban specified books from schools for containing inappropriate messages. One book banned was the poem “The Hill We Climb” written and performed by Amanda Gorman for the Biden inauguration, the single claimant that led to its banning mistakenly listing famous African American television personality Oprah Winfrey as the author, and objecting on the grounds that it was “not educational and have indirectly hate messages”. The hate messages cited by the claimant were:

“We’ve braved the belly of the beast. We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace, And the norms and notions of what ‘just is’ isn’t always justice.”

and

“And yet the dawn is ours before we knew it. Somehow, we do it. Somehow, we’ve weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished.”

Parallels with attacks on liberal thinkers by earlier fascist regimes are obvious.

The consistent feature of fascism as opposed to communism is that power is derived from the wealthy elite rather than the working class within society. It is notable that the increasingly extreme form of capitalism that has been practiced in recent decades has been accompanied by a general movement of the political debate to the right as socialism has been diminished, especially in the anglophone countries, but increasingly in all developed regions including the famously progressive northern Europeans.

This began as a consequence of ideological drift setup by circumstances arising immediately after WWII with the cold war and was exacerbated by the hubris within the west that accompanied the collapse of the USSR.

There was another major factor, however.

FDR was an incredible leader because he blended political realism with a deep optimism in and for humanity. He did not fear political consequences of falling out of favour with the elite in society, even though he had lived a privileged upbringing, and in many ways, he sought political advantage from being seen to occasionally annoy or even enrage the wealthy elite. The wealthiest businessman of the period, the banker J.P. Morgan, was a preferred target for FDR’s verbal attacks and policy measures to diminish the influence of the wealthy.

It is more than ironic, then, that nowadays the leader of JP Morgan Chase & Co, the legacy business of the original eponymous business, CEO Jamie Dimon is amongst the highest profile American businessmen who identifies as a Democrat, the left-wing party of FDR, and has a long history of significant monetary donations. Mr Dimon is considered by many as one of the most powerful men in America and is certainly one of the most acclaimed Wall Street power brokers leading the largest bank in America, indeed the largest bank in the world by 2023 market capitalisation, for over a decade and a half.

By the standards of 70s, however, the views of many of these wealthy elites who self-identify as being on the left of politics, and donate significant sums of money accordingly, would be considered well to the right side of the political divide. In fact, their actions and expressed views when compared with those of Charlie Munger’s, discussed earlier, who has been a life-long Republican, act as a clear of indication of how far the political centre has shifted to the right because Munger’s values are clearly well to the left of these other much younger elites.

This relationship between wealthy elites and the political centrality of society deserves examination not just with respect to observed affects but also as to cause.

As discussed earlier, lightly regulated political donations is one way in which political processes have been corrupted through legal means. The experience of the wealthy elites during FDR’s prolonged presidency surely taught them that it is not sufficient to only influence the right side of politics even if its long-term support for owners (of capital) through support for capitalistic markets provides a natural affinity. As the wealthy elites learned then, also, opportunistic support through large, one-off donations assures only ephemeral influence at best.

What was learned from their experience with FDR was that if enduring influence is to be achieved then it requires a good proportion of the wealthy elite being seen to be long-term supporters of the political left. And, since wealthy elites understand well the significance of always having influence, not only when one party is in power, there has been no shortage of wealthy elites prepared to be seen to be aligned with the left.

Well-known hedge fund manager Bill Ackman has even called on Jamie Dimon to run for the Democratic nomination for the 2024 Presidential election.

This factor is at least as important as any other in the drift of the political centre to the right.

With that the situation, for contemporary populist to gain significant attention they must be ultraconservative, whereas policies that in the 60s even Republicans considered seriously are cast as the realm of the far left.

While these circumstances explain the rightward drift in the political centre, so too were there natural circumstances that caused rightward movement of politics before WWII. The parallels between then and now are disquieting.

To any objective observer it is becoming difficult to see significant differences from the state of politics – fascism – which the Allies resisted and fought against in WWII and the one that America now has, and that distinction is growing less and less clear. In fact, this distinction could be lost with the election of another right-wing populist US President. The need to defeat a right-wing populist Republican candidate ensures the nomination of a right-wing Democrat.

The apparent or perceived phoniness of predominantly two-party systems where there is only very minor political difference and where both sides have been captured – through donations and other party or individual conflicts – by wealthy elites has been exploited by the populists to increase influence leading to increasingly fascist-like actions which the two parties struggle to oppose or resist. Given the influence American culture has on broad humanity, especially within anglophone regions, it is concerning how we have arrived at a moment in time where the dominant nation increasingly resembles a quasi-two-party fascist state with other major allies in danger of following.

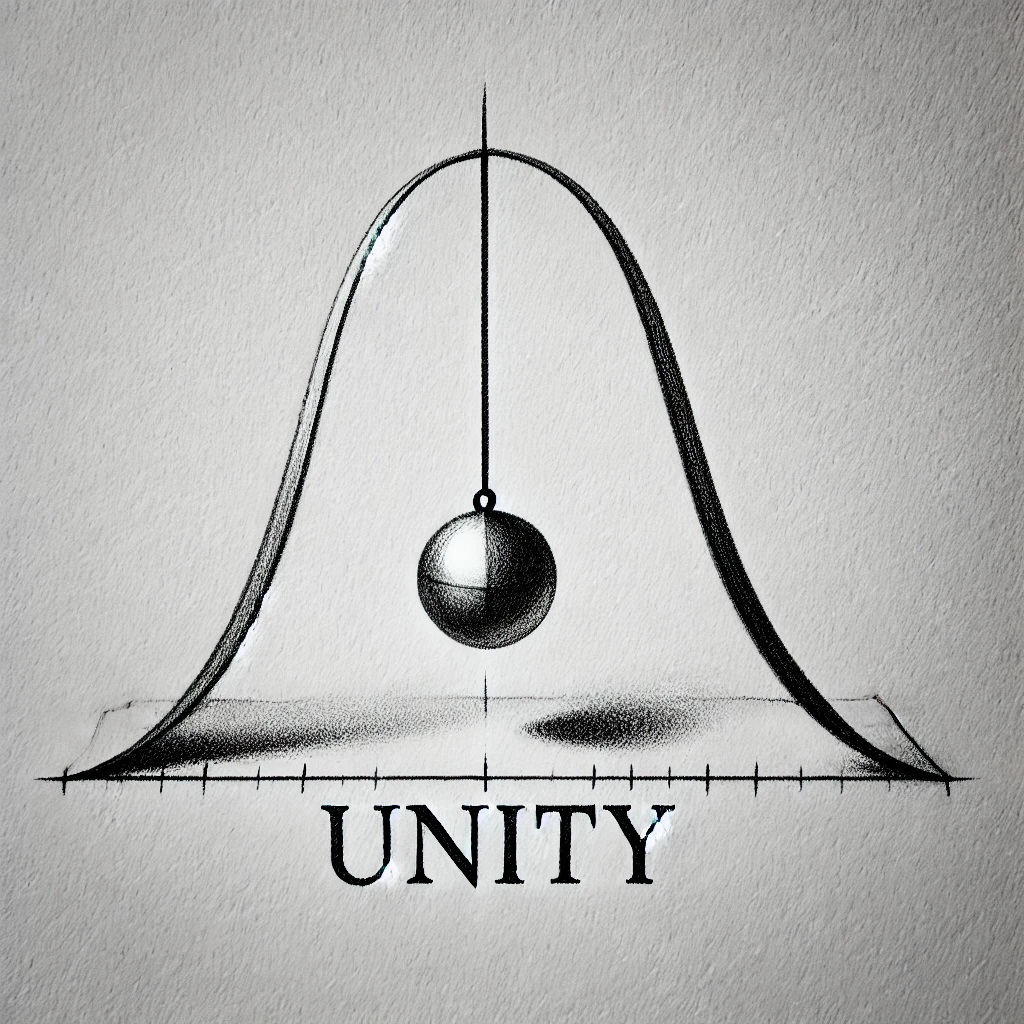

How have we humans managed to progress through so much division?

Human progress has often been conceptualised as a swinging pendulum because it so aptly describes not just the observable but also the experiential. Perhaps the greatest contest within humanity has been between wealth, the owners of resources whether it be land or other resources nowadays expressed as some form of money, versus the workers, those who do not own much in the way of resources so they must continually acquire their regular (often daily) needs through their own labour by being self-sufficient or by selling their labour in return for money with which necessities are purchased.

This push and pull has played out over the millennia since human beings aggregated into communities and began to specialise their skillset rather than being generalists doing everything for themselves.

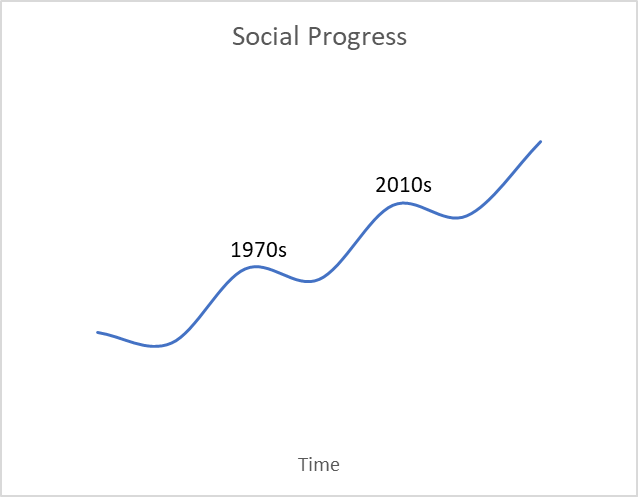

Those who lived through the second half of the 20th century, for example, would have witnessed and experienced in one way or another the power and influence of labour build up to an extreme largely through the instrument of collective bargaining with unionism into the 70s only for that power and influence to subside in the last decades of the century, even through reforms enacted by left-wing parties that are closely associated with unions.

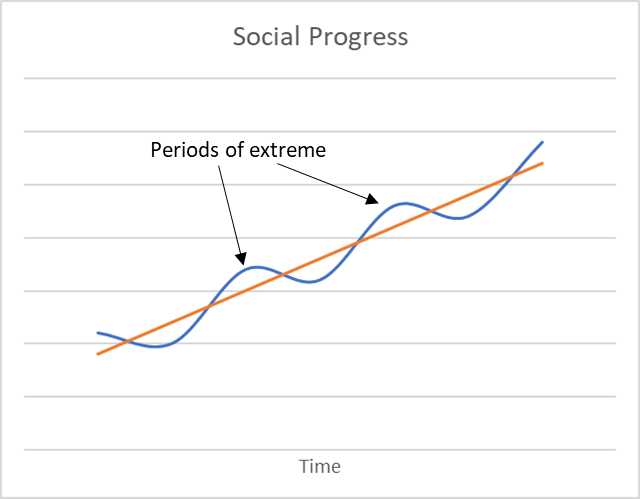

Though the pendulum concept is apt, it is not complete because it would suggest that humanity does not progress as the pendulum swings about a stationary point. If we zoom out and consider how humanity has progressed from the caveman days until now it is abundantly clear that we have progressed a great deal, so there has to be much more than this to social and overall human progress.

Human progress can be more accurately depicted as a swinging pendulum where the central point of the swing is on a continual upward trajectory. That is why it feels – depending on your position in society and your values – at times like progress has slowed or even gone backwards, and then at other times it feels like progress is accelerating. In the case of the swinging pendulum, imagine that the pendulum is instead viewed from the side so that the swinging action is no longer visible, and it just appears that the vertical string is shortening and lengthening, or perhaps it appears like the stick of an upside down (inverted) lollypop. With close observation over a period it will be noticed that the top point of the string or stick, the point of articulation, is on a steady upward trajectory. If the position of the swinging bob, which denotes humanity’s lived experience of progress, is traced it will in fact show a wavey line heading up towards the top right-hand corner even though there are times when the line is actually heading downwards.

This explains why sometimes it feels like change is happening very quickly, then at other times it feels like things are actually going backwards.

The tendency of humanity to be influenced to swing from one position to another in the opposite direction is exacerbated by populists who seek to harness these swings to advantage themselves by gaining political power, influence, and privilege. Such opportunists have historically been prepared to take the pendulum, and thus humanity, to the extreme to achieve their aims, and since this work started with the events of WWII it should be abundantly clear that Nazism and Hitler are patent examples of this.

Many feel that humanity is undergoing another period of extremism at the present moment, but at this present time it is difficult to know whether the pendulum has swung back or whether it is approaching the inflexion point. Either way, it feels to many like human progress is going backwards with the emergence of right-wing extremism in America and elsewhere.

This was underlined by the way the results of 2020 US Presidential election were no accepted by Donald Trump, by the measures he took and attempted to keep hold of power, and in the insurrection that occurred at the Capitol on the20th of January 2021 after he spoke to a crowd of his supporters.

Politicians on the right trying to out-Trump Trump in order to gain power have also had significant affects, and the aforementioned banning of books in the US has disconcerting echoes with the actions of other extreme political movements including Nazism.

This move to the extreme right is also associated with an apparent rise in racism generally throughout the world.

Even though elections are won by the team on the most numerous side of the centre, modern politics has become polarised in recent years by this move to the extreme right.

Taking humanity to extremes does nothing to aid human progress, in fact it hinders it for one very important reason. The more energy put into swinging the pendulum to extremes diverts attention from the real goal – to put all the resources of our collective human endeavour towards driving progress, in other words to steepening our actual trajectory of progress.

The only way that can be done is by having guardrails from strong social norms and laws on the basis of social cohesion that lessen the amplitude of the swing of the pendulum.

It is the force of the swinging of the pendulum which makes human beings feel uncomfortable – afraid of change – such that at extremes some, the losers, feel like they are barely hanging on while others sit atop the bob and drive it on to even greater extremes for their own benefit.

It is an entirely inefficient way for humanity to progress, it is hardly capitalistic given the level of resources wasted, and it is perhaps the greatest reason why humanity remains on an unsustainable path.

The best vaccine against crises is social cohesion

The climate crisis is the greatest crisis that humanity confronts. It is, perhaps, the greatest threat of our own making that humanity has ever confronted. To this point our response to climate change has been weak, variable, and slow primarily due to a lack of agreement over identifying the threat and then the measures required.

It would be nonsensical to suggest that a response to climate change, or any other crises affecting humanity, will not be forthcoming without improving social cohesion. Of course governments have and will continue to react when crises happen, as governments are now to the climate crisis, and as they did during the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the timeliness and quality of that response, and therefore the ability to manage the impacts to humanity, is highly dependent on the cohesiveness of societies both regionally and globally. And the COVID-19 pandemic underlined how the current poor level of social cohesion led to serious impacts along the divisive fissures in regional and global societies based on inequality whereby vulnerable peoples were so much more seriously impacted than the wealthy.

The COVID-19 response was inadequate in many wealthy nations. Few nations, however, reacted so poorly relative to their capacity for response as then President Donald Trump-led America, the wealthiest nation in the world, and the nation that humanity has looked to since WWII for global leadership and which, while coming at significant cost, has provided very significant preferential benefits to Americans. Instead of leading, the US President resorted to provocative language, which even the next President did not completely resile from, as aspersions were cast over the origin of the virus in a blame game to deflect attention from his inept leadership.

America also went AWOL on the climate crisis under Trump as he appeased the climate denialism that he had stoked. The serious challenges to agreeing, and even more critically, enacting, systematic responses to the climate crisis are deeply concerning to the global scientific community as well as those with the common sense to trust the views of those within humanity who chose to develop specialised skills in scientific research in areas related to climate and climate change impacts.

The future of humanity is too significant an issue to depend on only one global leader. Even if their political leadership is decided in fair elections, Americans are only a small fraction of global humanity, and that they hold a far greater share of global wealth is simply evidence of the inequality that America has done little to address.

A society that is always at war, and always must have an enemy, has become a danger to itself as well as others.

Moreover, there is no guarantee that America’s flirtation with the extreme right is over for now.

Humanity does not need a dominator. Power from wealth, no matter the various perspectives on whether it was acquired nobly or whether it was ill-gotten, does not grant a right to laud it over the majority.

Humanity needs supportive co-operation and collaboration. That is our evolutionary advantage, and it is does not preclude responding forthrightly when collective agreement is reached that it is required against recalcitrants.

In the mid-twentieth century two world wars provided the impetus for the creation of a global organisation as a force for an enduring peace. The first iteration – the League of Nations – was found wanting in its design, and after WWII the United Nations was created largely out of the vision of FDR.

While the United Nations has endured, it’s primary objective of securing peace was severely curtailed by the cold war, and it was no until sanctioned action in Kuwait in 1989 in response to Iraq’s invasion that the security council worked in the way it was meant to. Then in 2003 it was made a mockery of by an American administration bent on avenging the attacks on America property on the 11th of September 2001 that sadly caused the death of nearly 3,000 human beings who were in America at the time, a significant proportion of them being citizens of other regions.

Under President George W Bush, the son of George Bush Sr. who was President during the first Iraq war, America sought to broaden its retaliation to Iraq and the regime of Sadam Hussein after the success of operations to overturn the regime in Afghanistan where the terrorists that orchestrated the attacks had their bases. America and its key anglophone ally, Britain, told the UN Security council that they possessed intelligence that Hussein had weapons of mass destruction (WMD) that could be deployed in 45 minutes as a justification for unprovoked invasion to topple the Hussein regime. UN weapons inspectors led by Hans Blix, former Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, carried out approximately 700 inspections finding no WMD which was detailed in a report to the UN Security Council on the 14th of February 2003. Mass antiwar marches occurred throughout the developed world, with protesters in London alone numbering 2 million by the organisers.

Undeterred, America and Britain submitted a draft resolution to the UN stating that Iraq had missed its final opportunity to disarm peacefully, which France, Russia and Germany opposed. France and Russia on the 10th of March threatened to veto a UN security council directive to Iraq to disarm within 7 days. On the 17th of March America, Britain and Spain abandoned all attempts at securing an UN Security Council resolution authorising force and 3 days later America launched an invasion of Iraq through ‘Operation Iraqi Freedom’.

The Iraq war involved military and other personnel from 48 nations which America briefly dubbed the ‘coalition of the willing’, the majority being small nations whose support for the war was associated with large foreign aid offerings from America. The only permanent members of the UN Security Council involved in the conflict which officially lasted for over 8 years were America and Britain. Exact numbers are impossible to determine, but civilian casualties ran into the hundreds of thousands and the region remains politically unstable today.

Hans Blix maintained that America and Britain dramatised the threat of Iraq having WMD to justify the 2003 attack, and furthermore believed that he was the subject of a public smear campaign and that American intelligence operations were conducted to undermine his credibility in an echo of the ‘reds under the bed’ era of false accusations and political attacks.

The leaders of the allied anglophone nations who supported the American invasion of Iraq, to give some level of suggestion that the operation was not unilaterally America on its own, especially Tony Blair of Britain and John Howard of Australia, did not resile from the fact that foremost in their aims was to maintain a close relationship with the dominant ‘super power’.

I intentionally suggested that these actions were to avenge the attacks on American property not the actual deaths of Americans for a very specific reason. At the height of the recent COVID-19 pandemic 3,000 American lives were lost daily, a very high proportion of them preventable if American leadership responded in a way which honoured the primacy of human life above other considerations, a demonstrable fact when mortality rates are compared with other developed nations including my own of Australia, New Zealand, and indeed, in China. These nations proved that protecting lives in the COVID-19 pandemic was indeed a matter of priority and will. Instead, the American President, Donald Trump, prioritised economy and wealth saying, “This is America – we can’t just shut things down!”. Of course, that was necessary anyway when medical facilities were overrun with seriously ill and dying patients, and when the dead were piled in refrigerated containers and buried temporarily in parks. Then to deflect attention from his own inaction which brought death and misery to many American families, at every turn he looked to sheet home blame for the pandemic to China, the country which experienced the first large scale deaths in the pandemic. Trump found an ‘enemy’ to blame.

It is clear, then, that the loss of human life was not the true driving force in American culture to support actions against nations, more specifically against certain leaders of or within those regions, which had shown their dislike for American culture – it was to avenge an attack on American prestige and power.

Any objective reader, who read his words as sincere, surely would find it challenging to reconcile a view that the man who left humanity as its leader on the 12th of April 1945 could be truly proud of such an America.

This seems unrecognised, however, presumably because those who wish to cast aspersion on his legacy question the sincerity of FDR’s words as a veiled nod to the inauthentic fashion with which many politicians behave. This ignores the repetition of his stated intent, his demonstrable efforts to establish a lasting peace amongst humanity, and perhaps most importantly, it is absent emotional connection with the context in which he led his constituency which he undoubtedly felt extended to all of humanity.

It is often said that it is the winners who write history. The experience of post-WWII shows that it is more than that – it is those within the winners who survive the longest and who have the loudest voices that get to influence what is perceived and or remembered from our history.

America and its historical allies conveniently dismiss their ‘enemies’ as evil because it stops us from engaging in a deeper examination of ourselves.

That is the importance of the “Rücksetzen” timeline where the extreme elements of a German-dominant society post-WWII are stripped away – i.e. the Nazism and associated Lebensraum extraterritorial conquering – instead adopting Schachtian neo-Weltpolitik whereby Germany is the dominant economic power within humanity with its ingrained harshness never reconciled or acknowledged.

All alternate realities invite an examination of the ways in which the imagined history differs from lived experience. What, then, are the difference between that alternate history and the America-dominant humanity that has been experienced for almost 80 years. Does it extend beyond simply which group of human beings have exerted their privilege for their own betterment, with any concomitant improvement or worsening in the situation for others simply incidental?

That is for the reader to consider.

What I will say is this. My own experiences at the beginning of the 21st century suggest that even in German society, the one society which has not been allowed by broader humanity to minimise the extreme consequences that follow hate on racial and other narrow ultraconservative ideals, the lessons of prejudice and hate were not sufficiently embedded to establish lasting inclusive social cohesion.

What will it take?

Quality globalisation

Globalisation refers to deepening connection between all human beings.

It is furthered by more frequent and authentic connection irrespective of the geography in which people reside. While globalisation is entirely a matter of human connection, in reality a humanity that has concentrated on economic transactions has tended to concentrate on human connection that facilitates an economic exchange, almost inferring that this type of connection is the only one of worth to humanity.

Nothing could be further from the truth as this treatment highlights.

It might be easy to justify this mistaken focus on it being the first type of globalisation humanity experienced – i.e. the wealthy European colonialist nations exploring and seeking out land and resources from which intercontinental trade was fostered – this, too, ignores the reality that indigenous peoples did undertake long trips without seeking economic returns but only out of curiosity and a desire to learn from and connect with others.

During a period of increasingly extreme capitalism, there is a tendency to search for economic value to all human activities. So let’s look at recent experience for what such globalisation has delivered.

COVID-19 laid bare the truth of economic globalisation. Nations that have remained poor were impacted seriously because they lacked the health system to respond, and they lacked the social infrastructure to protect people from direct impacts of the virus on them and close connections as well as shield them from the economic impacts.